The 2016 World Endurance Championship was closely contested between three manufacturer teams: Porsche, Audi and Toyota. In 2015, Toyota had a pretty rotten season, it being clear early on that the car simply wasn’t quick enough, and attention turned to the development of a car that would be better able to contend against the two siblings from Germany. Whether or not Toyota succeeded is not necessarily as easy a question to answer as it might seem, as a look at the championship positions is really too simplistic.

Similarly, one might argue that Audi came into 2016 with a significantly upgraded version of its R18 e-tron quattro; a car that was fast, but fragile, and one that failed to do itself justice over the course of the season.

I have had many such discussions with people since the season ended in Bahrain last year, and – as is my wont – I have spent some time trying to work out how best to answer these questions objectively, using the data that I have managed to collect over the season.

I would like to think that, if you are reading this, you might also have read my piece about Aston Martin’s season in the GTE-Pro class, and how it was affected by the Endurance Committee’s decisions in their attempts to Balance Performance. It is here if you haven’t.

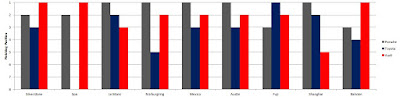

In any case, the method that I use there, and that I am going to use in this analysis, is to base an assumption that a car’s outright performance can be judged by looking not at its single fastest lap in the race, but in the average of the best 20% of green laps in the race. Taking the best car in each race by this measure, and then comparing the competition as a percentage against this, reveals how much slower each car was, relative to the best.

Over the whole season, this data looks like this:

(I know, this is far too small to read... click on the image, to make it bigger!)

Also, in preparing these numbers, I have taken only the better-performing car from each manufacturer. At Silverstone, the figures for the no. 1 Porsche, the no. 5 Toyota and the no. 8 Audi are based only on the first green period before the FCY.

A common assertion these days is that endurance racing is a sprint, from start to finish. There is no room for taking things easy, for looking after the machinery. In the pits, there is not a lot to separate the teams. It is all down to the quickest driver and the quickest car. Well, yes it is; but that doesn’t tell the whole story either. If it did, then the results of each race would reflect the graph shown above.

To make this easy to compare, I show below the finishing positions of the best car from each of Porsche, Toyota and Audi in each race.

The obvious conclusion from this is that only Le Mans and Bahrain provided race results that were true representations of the performance of the cars in each race. And anyone who was at Le Mans will know that the result of that race was hardly what had been expected either.

This view is too simplistic though, since the finishing position does not show the relative distance between cars at the end of the race. Instead, we should look at this, which shows the average speed over the whole race, as a percentage of the winner.

This shows much better how close the races were, particularly in the latter part of the season. In the first two races of the season, Audi was able to convert its performance advantage into victories. At Le Mans though, the “car with the four rings” was simply not fast enough. Their podium at the Circuit de la Sarthe only came at Toyota’s misery. It is interesting though, that Toyota had a car that was not as quick as the Porsche. Although Toyota had a clear performance disadvantage at Mexico, the margin by which they lost the race was very small.

After Le Mans, the performance of Audi (in particular, the number 8 car) was outstanding: in terms of speed, the car was only beatable at Mexico and Shanghai. The fact that this was not translated into victories is evidence that there is still – thank heavens – more to winning a race that just being fast. The points table could have looked rather different if Audi had capitalised on these performance advantages.

The fact that the performance graphs are so different from the finishing position and race speed graphs underlines the fact that there is more to the WEC than speed alone. Drivers are correct when they give credit to the team for success. And having fast drivers and a fast car is not enough to win titles, as Audi has proved in 2016.

Creating a winning squad is an art – the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. It will be interesting to see who has put the pieces together most effectively in 2017.

Tuesday, 17 January 2017

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Hi Paul, Interesting reading as always. I wonder how this relationship between outright pace and overall results will be affected by going from 3 to 2 manufacturers, and then from 2 car teams to (potentially) 3 car teams.

ReplyDeleteWill the correlation get stronger as there's more "bullets in the gun" for each team and so a higher chance that a car of the fastest chassis ultimately wins/finishes strongly.

Or will the correlation weaken. Meaning the picture of the starting grid looks completely different to the finishing order. As with less total numbers of LMP1-H cars in the class, and only 2 teams duking it out meaning more risky strategies will be at play in an "all or nothing" mindset to beat the other team. All in which introduces more variables to shakeup the finishing order.

As ever, an interesting season awaits!