The A6-Am class requires teams to lap outside the “minimum reference lap time” of 2m 03s (or 2m 05s if in the so-called AM-BOP advantage sub-class). Often this has proved a recipe for success in overall terms – Hofor Racing having come home fourth overall last year, and Dragon Racing’s Am-class Ferrari having finished on the overall podium in 2015. This year’s race was different in that respect, though. The first six cars in the overall classification were all in the A6-Pro class.

The top six consisted of three Porsches, two Audis and a Mercedes, the only other contenders for the win, Lamborghini, having fallen by the wayside with various problems. In the end, it was not a nail-biting finish, the main point of interest in the closing stages being the fight for second place between the Manthey Porsche and the second-string (no. 3) Black Falcon Mercedes. That’s not to say it was a race without interest; with strategy, tactics and incidents aplenty throughout the race to hold the attention.

Famously, the Herberth Porsche 991 GT3-R had Brendon Hartley on its driving strength, and once again the plain white Porsche was a picture of perfection – not only running faultlessly for the entire 24 hours, but also running fast enough to match the lap times of all but the Black Falcon Mercedes AMG GT3s. Its victory was well-deserved.

It was no real surprise to see Hartley slotting in smoothly, without disrupting the low-key approach of the team. The World Endurance star neither hid from nor hogged the limelight, and seemed to revel in the whole experience. Arguably, the race fell to Herberth as a result of two incidents on the track, which significantly delayed its two chief rivals. The more significant occurred just before dawn, when Khaled Al Qubaisi took the wheel, for the first time, of the no. 2 Black Falcon Mercedes that had been right at the front of the field up until that point. Contact on the 11th lap of Khaled’s stint inflicted sufficient damage to the AMG to render it hors de combat for the remaining seven hours of the race.

Much earlier in the race – in fact after just three hours had elapsed – Otto Klohs, in the Manthey Porsche, was on his first ‘out’ lap when he had a coming-together, resulting in a delay returning to the pit and an unscheduled pit stop while repairs were affected (and no doubt the driver’s confidence was restored).

Psychological factors aside, the incident on the track and Klohs’ lap back to the pits cost it around 40s, and the repairs cost a further 1m 20s. Taking account of the Code-60 under which the stop took place, the total time lost (compared to the Herberth Porsche, which was at that point behind the Manthey car) was around 2m 30s. Herberth’s winning margin was two laps, or 4m 46s, so to say that the incident cost them the race is probably over-egging the pudding somewhat, but at least they might have been able to challenge, and exert some pressure on the (unflappable) Herberth crew.

Whatever the ‘what ifs’ and ‘maybes’ were, the true strength on Herberth Motorsport’s side is their consistency. The balance of the driving line-up is far better than most of their competitors. For Herberth, unlike Black Falcon, the drive time regulations seem to have no impact at all on the strategy.

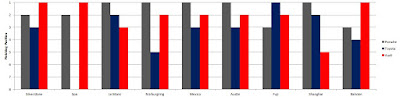

It is always interesting to compare the driving times of the individual drivers in each crew, and this is shown below. Hopefully the colour-coding helps.

Finally, a look at lap times. For the purposes of the tables below, I show both the best lap achieved by each driver in each of the top six cars, and also their “best stint” time. This is derived by taking the average lap time for the stint by ignoring the ‘in’ lap, the ‘out’ lap and any laps affected by Code-60. I have also, for this purpose, ignored the opening stint for each car, since the three or four laps of traffic-free running skews the average significantly. Inevitably, however, this leads to some averages being from a much smaller sample than others, and of course the track conditions change over the course of the race, so I am aware that some of the figures may be misleading. Nevertheless, the comparisons are interesting.

| 911 Herberth Porsche | Best Lap | Best Stint Ave |

|---|---|---|

| Daniel Alleman | 2m 01.310s | 2m 03.6s |

| Ralf Bohn | 2m 01.808s | 2m 04.2s |

| Robert Renauer | 1m 59.516s | 2m 02.4s |

| Alfred Renauer | 2m 01.506s | 2m 03.1s |

| Brendon Hartley | 2m 00.514s | 2m 02.1s |

| 12 Manthey Porsche | Best Lap | Best Stint Ave |

| Otto Klohs | 2m 05.092s | 2m 06.3s |

| Jochen Krumbach | 2m 01.534s | 2m 03.8s |

| Matteo Cairoli | 2m 00.077s | 2m 02.1s |

| Sven Müller | 2m 00.321s | 2m 02.3s |

| 3 Black Falcon Mercedes | Best Lap | Best Stint Ave |

| Abdulaziz Al Faisal | 2m 00.942s | 2m 03.5s |

| Hubert Haupt | 2m 00.979s | 2m 02.1s |

| Yelmer Buurman | 1m 59.198s | 2m 02.4s |

| Maro Engel | 2m 00.194s | 2m 02.5s |

| Michal Broniszewski | 2m 03.108s | 2m 04.9s |

As always, I am happy to hear your comments, so do let me know if you have any!